via AUSTIN: Planning Commission Recommends Domain On Riverside Amid Protests

Anti-Gentrification Group Makes Bonfire Out of Art-Washing Magazines

By Jamie Haynes

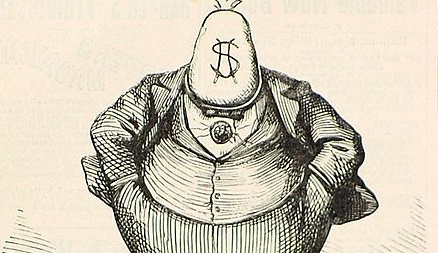

Wednesday night, Austin organization Defend Our Hoodz – Defiende El Barrio (DOH) continued their offensive against Presidium Group’s scheme to leverage a “pop up arts’ district” into zoning changes that threaten to accelerate the systematic displacement of working class and student populations living in the Riverside neighborhood.

Rally goers passed out hundreds of flyers, chanted slogans, and destroyed copies of Almost Real Things, self-described as an “Art zine for the in-progress andsoon-to-be.” By in-progress I assume they mean gentrification and soon-to-be the Domain 2.0 on Riverside.

According to dozens of community members who participated in the demonstration, these outcomes are neither desirable nor inevitable as evidenced by the continued string of victories DOH has won over Presidium Group’s lawyer Michael Whellan and property managers like Logan Stansell.

Dallas-based investors from Presidium own 17 large scale properties in Austin and are working with city officials to implement zoning changes which would allow them to extract enormous profits from the eviction, destruction, and reconstruction of…

View original post 453 more words

Austin “Non-profit” Southwest Key Raking in the Cash

The City of Austin, University of Texas, and Travis County should cancel all contracts with Southwest Key Programs, Inc. (SKPI) until they suspend their child detention facilities. El Presidente/CEO Juan Sanchez may have started the organization with the best of intentions, however SKPI has lost its way.

I spent some time reviewing the 2015-16 Form 990 SKPI filed with the IRS and was dismayed at what I found. Essentially there are two arms of the organization, the nonprofit Southwest Key Programs which is responsible for federal contracts and East Austin College Prep (EACP), the other arm is a holding company named Southwest Key Enterprise which according to the filing, “does not create goods or offer services to the public itself; its sole purpose is directing the management of the for-profit subsidiaries.”

The for-profit subsidiaries and exorbitant salaries of senior leadership are just one of several ways public dollars are siphoned off into private industries with little public oversight in regard to contracts and budgeting.

One example is, “Southwest Key Café del Sol, LLC (the “Café”) is a small Mexican-American café located at Southwest Key Headquarters that produces delicious and affordable food for the East Austin community.” Sounds innocuous enough, until you see that they are also responsible for providing catering and food service for their charter school and multiple family and child detention centers across five states.

Southwest Key charged the federal government nearly 4.8 million through the school lunch program reimbursement and the café brought in an additional $687,832 in 2015-2016. Others may argue that the nonprofit does meaningful work in the areas of juvenile justice and marriage and parenting classes, but closer examination reveals spending priorities.

Southwest Key spent less than $60,000 on healthy marriage and responsible father programs, but $221 million on its unaccompanied minors detention centers and associated costs. When you add the $227 million spent on education programs here locally and in their centers, you begin to understand why Southwest Key Enterprises contains eight firms responsible for tasks all directly related to the delivery of the non-profit services, it is a lucrative business.

The subsidiaries include not only the food service company but also: maintenance, green energy and construction, real estate holdings, floral services, workforce development, transportation, and data and evaluation. Their for-profit status means there is no ceiling on employee salaries or what the companies can charge the parent non-profit for services rendered.

It is highly unlikely that the spoils from these contracts proportionately benefit the many direct-care workers or the children and families they are meant to serve. Highly unlikely because, according to their 990, the for-profit entities earned nearly $19.6 million in revenue. Overall the company increased net assets by more than $16 million in a single year. The top six executives combined earnings were over $1.5 million, averaging about $260,000, that’s right more than a quarter of a million dollars. Not bad for a mom and pop nonprofit.

These salaries do not include bonuses which pushed CEO Juan Sanchez’s individual earnings alone to nearly $1.5 million last year. Equally concerning is that the board of this huge enterprise only consists of six members. Orlando Martinez, former commissioner of Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice whose LLP uses intimate knowledge of policy to leverage programs for juvenile offenders. Southwest Key operates in Georgia.

Anselmo Villareal, CEO of La Casa de Esperanza charter school near Milwaukee whose Café Esperanza is strikingly similar to Key’s Café del Sol. Southwest Key is also active in Milwaukee and Juan Sanchez is on the privately appointed school board for Esperanza.

These are but two examples which aptly demonstrate the way federal policy is leveraged to line the coffers of non-profit and for-profit providers alike. Another hidden aspect is the way South West Key’s real estate contributes to gentrification through expanding the property tax base. Additionally, when EACP enrolls students, who otherwise could go to AISD, the district loses money and the district’s burden under recapture is increased.

Rosa Santis is another board member with a well-known history of real estate development in east Austin. A global technology firm’s management consultant, local insurance agent, and a retiree from Veterans’ Services round out the board. I think all they are missing is a banker. Follow the money and you find a deeper story of profit built on pain. Until Southwest Key stops making millions of dollars off others’ misery, the city and county should end their contracts, UT Austin should stop providing social work interns for free labor, and parents should withdraw their children from East Austin College Prep.

Linda Darling-Hammond: Can Public Education Survive Betsy DeVos?

Linda Darling-Hammond surveys the wreckage of the privatization movement and assesses whether Betsy DeVos’s failed policies in Michigan will inflict further harm on the nation’s embattled public schools.

The article is well worth reading. It contains useful data.

However, I have some caveats.

I greatly admire Linda and her scholarship, but we have a fundamental difference about charter schools. As currently configured, I see them as an integral part of the privatization movement. She thinks there are good charters and bad charters. This is true, but the charter idea itself has been captured by people like DeVos who are hostile to public schools and equity. I agree with the NAACP that no new charters should be created until charters meet the same standards of accountability and transparency as public schools, and stop cherry picking the students likeliest to get good test scores. The good charters, in my view, should be…

View original post 378 more words

School Choice: It’s Common Sense? Installment 3.5 Wormhole

Before returning to the accountability history of Johnston and Eastside Memorial, I would like to take a moment to share some remarks from a recent school board meeting where I critiqued the proposal to move the Liberal Arts and Science Academy (LASA) to the former site of Anderson High School (the school for African Americans under segregation) in East Austin. (LASA’s influence at Eastside Memorial is discussed in last weeks post)

(LASA) is a selective public magnet high-school. The demographics of the school ethnicities are 23% Hispanic, 3% Black/African-American, 51% White, 20% Asian, 2% American Indian, and 1% Hawaiian/Native Pacific Islander for a total enrollment of 796 students (Lamb, 2014). LASA is collocated within LBJ High School (LBJ), LBJ is an Early College High School with different ethnicity/race demographics: 30% Hispanic, 39% Black/African-American, 15% White, 1% Asian, 14% American Indian, 1% Hawaiian/Native Pacific and a total enrollment of 648 (Lamb, 2014). Counted as one school, on paper LBJ and LASA are a model for racial diversity and their closely related socioeconomic status indicators, but in reality the two schools are worlds apart.

LBJ may have college in its name but on average sixty-six percent of the students agree with the statement, “I will go to college after high school,” thirty-four percent say “maybe” (AISD, 2014). At LASA ninety-three percent of students say “yes” and six percent say “maybe” (AISD, 2014). Even the response rates to the survey of both schools is telling. LBJ was sixty percent, LASA was eighty-eight percent, and the district average was seventy-three percent on the Student Climate Survey. Not only are students from the neighborhood being served by LBJ less likely to participate in sharing their voice, but students are also less sure that college is in their future. On the other hand LASA students not only show greater participation but also have generally more optimistic perceptions of their school climate.

It is with the above passage in mind that I drafted the subsequent citizen’s communication last week at the Austin ISD board meeting:

“Janelle Scott points out that historically the imposition of middle-class values and pronouncement of the liberal creed of “pulling yourself up by the bootstraps,” is heralded by white men claiming to know what the best course of action should be.

The choice the Austin school district made to house its most prestigious academic track at LBJ did not occur in a vacuum but was influenced by a historical context white consultants from Washington DC are likely ignorant to. A desire to both recapture students leaving due to white flight as well as to increase enrollment in an economically and racially stratified part of Austin drove the district’s initial placement of the magnet schools at Johnston and LBJ, subsequent consolidation, and is driving the proposal to relocate the campus. I argue that one of the major reasons the school choice movements has come to flourish is because rather than confront the glaring inequalities of a society stratified by race and class by standing up to the underfunded mandates of TEA and teaching critical pedagogy and Praxis, public schools allow the same disparate outcomes as separate but equal under the guise of equal opportunity in a post racial society. Researchers describe schools like LBJ as characteristically displaying “higher-than-average suspension rates and lower-than-average graduation rates” (Fabricant & Fine, 2010 p.121). Therefore the STAAR test serves to discipline LBJ while simultaneously ennobling LASA to participate in social reproduction and white supremacy. In 2014 26% of LASA students were nonasian minorities, that number is nearly three times as much, 69% of students at LBJ are nonasian minorities.

Magnet schools, like LASA, take on air of democratic equality, but from the brief example above there is little equity in a system where some parents can choose and participate in the best public education has to offer, a choice often accompanied by the social capital to be informed about the program, and the ability to afford the supplemental supports- academic, social, and communal- to make their child a viable candidate. On the other hand, parents at LBJ have a reduced ability to choose based on broader historical, racial, and economic contexts. Contexts which are tertiary concerns at best when consultants are hired to evaluate facilities and efficiency in an ahistorical fashion.

Therefore I ask that Black Anderson (now the Alternative Learning Center) not be repurposed to house LASA, Representing the erasure of culture, perpetuating the burden of desegregation disproportionately placed on our African American community, and representing the final gentrifying nail in the east Austin cultural coffin”.

*Photo Credit for this installment goes to Rodolfo Gonzales retrieved from: http://preps.blog.statesman.com/2015/06/11/prepped-and-ready-reviewing-the-2014-15-school-year/

School Choice: It’s Common Sense? Installment 3- Nomenclature

Johnston High School, in Austin, Texas was the first school in the state to be closed (rather than reconstituted) by the Texas Education Agency (TEA). The high-stakes accountability defined by No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was after all incubated in Texas under then Governor Bush. Senate Bill 618, passed in 2003, which codified school reconstitution for schools failing to meet the mark two years in a row. The bill aligned with NCLB, the 2002 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and signaled an end to local control; 135 schools in Texas were reconstituted in the ensuing decade (Cumpton, 2015). The closure of Johnston in 2008 and subsequent repurposing as Eastside Memorial High School at the Johnston Campus is an opportunity to witness the intersection of market-based reforms, racial identity, community history, gentrification, community organizing, and educational decision making. The confluence of macro political and economic forces cannot be ignored when examining the intersection of public school policy and private interests due to their impact in shaping individual and organizational perspectives (Kamat, 2004 p. 156).

History:

In 1959 Riverside High School opened to serve the graduates of East Austin’s predominately Hispanic Alan Junior High. A year later the school would be renamed after Albert Sydney Johnston, a soldier in the Republic of Texas, United States, and Confederate armies (Bearden, 2011). Austin, like many urban centers, began to experience white flight following Brown v. Board in 1954. Despite the Justice Department’s approval of a desegregation plan for Austin in 1955, it was not until after a 1971 U.S. District Court Judge’s ruling that Austin ISD was forced to implement bussing (Cuban, 2010).

Neighborhood schools’ attendance boundaries were redrawn to allow for two-way bussing. Previously the closure of the historically African American Anderson High School placed the burden of bussing and integration on the East Austin community (Cuban, 2010, Interview 5, 6, 9, 11, & 13). Following District Court Judge Jack Roberts ruling to implement a three tiered approach to desegregation which included two-way bussing, affirmative-action hiring processes, and bilingual education, the federal government provided 3.4 million dollars in emergency aid for the district (Reinhold, 1983).

The 1980’s were a time of significant change for Johnston High School due in large part to judicial and state bolstered financial intervention. Johnston became a nationally recognized model of school desegregation as its demographics shifted from 99% Hispanic and African American to 50% White, 30% Hispanic, and 20% African American, a population more reflective of Austin’s overall racial composition, and reduced the number of students below grade level in math from 90% to 52% (Garcia, Yang, & Agorin, 1983 p. 95). President Ronald Reagan even cited a Time Magazine article featuring Johnston, as a model of community investment without the interference of the federal government in transforming the community, apparently not recognizing the federal judicial and financial interventions which were instrumental in bringing about the change (Reinhold, 1983).

Increased funding for the school allowed for investment in renovations, technology, and expanded course offerings. This change in trajectory though was short lived. Austin was absolved from its federally mandated desegregation in 1983 and formally ended bussing in 1987 returning to neighborhood schools and the de facto segregation and lasting impact of restrictive covenant, residential housing patterns, and the bisection of the city by Interstate 35 (Cuban, 2010).[1]

In Austin, magnet schools of “choice” were an attempt to attract white, middle-class families to the Eastside schools through tracked prestigious academic and arts academies insulated from the comprehensive neighborhood schools within which they were collocated (Cuban, 2010). The LBJ Science Academy opened in 1985 and Johnston would be home to the Liberal Arts Academy starting in 1987 when two way bussing was discontinued to prevent another round of white flight.

Johnston did maintain its vocational programs and magnet status which built on a community tradition in providing vocational education for a predominately Mexican-American and Chicano community (Interview 7, 15, 19). However with ever increasing emphasis on achievement scores, enrollment and graduation rates continued to decline, and by the late 1990’s Johnston saw a thirty percent spike in already inflated teacher turnover (Reeves, 2007). The subsequent decision by the district to relocate the magnet arts academy to LBJ high school in 2002 only served to exacerbate already tenuous circumstances. The parallel histories of school choice, at the local and national levels, indicate the interconnectedness of education policy from the top down. Therefore, interruption or resistance to these types of reforms indicate that there is also a potential to influence policy from the bottom up, setting the stage for Pride of the Eastside.

-To be continued.

[1] For more information on Austin’s mixed history of progressivism and discrimination see Eliot Tretter’s work: Austin Restricted http://projects.statesman.com/documents/?doc=1499065-austin-restricted-draft-final

Dainanko

Dad is foreign, just like Buddhism which I embrace.

Why do I find it so hard to embrace my father?

Is it abandonment; is it a result of my past causes?

Actually none of that matters because it is up to me to change, because I chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo and he don’t.

Won’t capitulate,

Won’t strike like a rattlesnake,

The battle shakes my core.

Awakening like Kate Chopin.

No ma’am, Gulf of Mexico you won’t take me!

Cause I have agency and strength,

Frequency and length,

Like chords,

And cords,

The boards can be used as a plank, a coffin, or a boat.

Two sink one floats.

It’s like a hundred foot moat and I can’t even cross one ten feet, he’ll I can’t even touch the rim.

So my chances are slim,

Unless I reach out

Erase doubt.

Bail slander from my life and replace strife and all those rife adjectives that bring the pain.

I tend to forget about the sun every time there’s rain,

But because there is pain,

Then also joy is present.

Like all those letters unsent.

School Choice, It’s Common Sense?Installment 2: New Policy Networks Emerge

Johnston High School, in Austin, Texas was the first school in the state to be closed by the Texas Education Agency (TEA). The closure and subsequent repurposing as Eastside Memorial High School at the Johnston Campus is an opportunity to witness the intersection of market-based reforms, racial identity, community history, gentrification, community organizing and educational decision making. The confluence of macro political and economic forces cannot be ignored when examining the intersection of public school policy and private interests due to their impact in shaping individual and organizational perspectives (Kamat, 2004 p. 156).

This case of how IDEA, a privately owned public charter school, with significant institutional support, was met with resistance from the community it was reputed to serve, provides a unique opportunity to examine how a diverse group of individuals organized and acted on both sides of the issue. In particular, this case of community resistance and ultimately vindication demonstrates the democratic possibilities when communities are faced with state directed take overs and other top-down school reforms we will undoubtedly see under the Devos regime.

Background on School Choice in Texas

Texas, like Washington D.C., embarked on its own efforts toward reform during the 1980s. Texas Governor Mark White, pressured by business interests, appointed Electronic Data Systems founder Ross Perot to chair a special committee on education (Cuban, 2010). Their report, eventually signed into law as House Bill 72, instituted “no pass no play,” and included new education objectives and standards, required achievement testing, equalized district funding from the state, referenced charter schools, and strengthened top-down accountability measures (Cuban, 2010). The appointment of Texas business leaders to the helm of education reform echo similar trends in tailoring education to the “needs of the state” dating back to the early 1900’s (Kliebard, 1987, p. 99). The economic interest of the state benefits from the common sense that students should be prepared for employment and self-sufficiency.

New policy networks include alliances between the business community or chamber of commerce, legislators, think tanks, educational philanthropy, and school regulatory commissions. Policy shifts over time in Texas represent a movement toward market based reforms like an increased emphasis on competition through the expansion of charter school organizations associated with new policy networks (Debray, et al., 2007; Anderson & Donchik, 2014). New policy networks contribute to the inception, promotion, and ultimately legislation which benefit privately run public charter schools like IDEA.

The history of IDEA Public Schools dates back to 1998 when two Teach For America alumni, Tom Torkelson and JoAnn Gama, founded an after school program in Donna, Texas. In 2000 the state granted the Individuals Dedicated to Excellence and Achievement (IDEA) a school charter. The following should serve then as no surprise when an IDEA administrator Mx. Bishop shares,

Understanding more how the private sector can be a more constructive partner in helping address issues of equity, race, social justice, including education, but also affordable housing, and the revitalization of distressed communities. I just thought there was a lot more that the private sector could do…. I became aware of IDEA Public Schools when I was a staff member in the Texas legislature… I had a meeting with the CEO Tom, identifying, basically find legislative ways to improve equity in funding for public charter schools. (Interview 14, 2015)

This quote illustrates the articulation of discourses on equity and revitalization with the private sector. This resonates with the propensity of neoliberal economic policy “…to bring education, along with other public sectors, in lines with the goal of capital accumulation and managerial governance and administration” (Lipman, 2011, p. 14).

A Closer Look at the Influence of New Policy Networks

According to and AISD Trustee, Mx. Holbrook, the vetting process for IDEA Public School’s contract with Austin ISD spanned one year (Interview 7, 2015). However, Austin ISD identified IDEA Public Schools as a potential partner during the initial reconstitution of Johnston High School in 2008. To be fair, there is some evidence as to the efficacy of in-district public charter school collaboration, the good sense of cooperation found in the common sense of school choice (Gulosino, & Lubienski, 2011). However, this partnership warrants further examination due to the influence New Policy Networks appear to play in facilitating the process (Debray-Pelot et. al, 2007).

In 2008 AISD asked for assistance from the Texas High School Project which is an arm of Communities Foundation of Texas, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Michael and Susan Dell Foundation. According to their website, Communities Foundation of Texas started in 1953 in Dallas through the efforts of various business and civic leaders. Contributions of land and charitable gifts built the organization, and a tax law change created a larger incentive for contributors to donate to community charities rather than private charities. In the sixties the foundation expanded its scope and began focusing on free enterprise stating, “Though times have changed, the Institute’s mission remains the same – to offer education and training for today’s entrepreneurs” (CFT, 2016).

The Texas High School Project was launched in 2004 in order to “create meaningful change for Texas students. By strategically connecting the diverse stakeholders committed to this cause — from legislators and funders to business and civic groups to school administrators and teachers — Educate Texas is leveraging the power of collaboration, bringing together resources and expertise” (CFT 2, 2016). In addition to helping schools with redesign initiatives the group was successful in bringing 20 Charter Management Organizations to scale and invested thirty-five million in capital, “to achieve tenfold growth and maximize the alliance’s statewide impact” (CFT 2, 2016). The emphasis on small schools and technocratic solutions to education challenges are some of the hallmarks of both the Gates and Dell foundations (Debray-Pelot Et. al, 2007; Burch, 2009). The partners helped AISD find entities that met the criteria of open enrollment, governance, capacity, technical assistance, cost, and external partnerships.

The resulting document of recommendations made specific mention of IDEA Public Schools as a potential partnering entity should they be willing to convert their state charter to a district charter conversion based on IDEA’s connections to external partnerships (AISD September 22, 2008).

To be continued in Installment 3.